As a woman in GLAM— that is “galleries, libraries, archives and museums,” art is constantly at the forefront of my mind. I see references to works I love and have studied in almost everything and I’m constantly connecting theory to media and pop culture. That is to say, art is a foundational part of who I am. It is intrinsic to my existence. And nothing makes me happier than recognizing and highlighting the ways in which who I am and my love of art interconnect and overlap. One of my favorite things about being Black American is the ways in which Black American artistic production has pioneered and pushed the needle further in every field and sector we touch— especially within the context and confines of creative genres, such as, visual art, music, television, film and pop culture.

And while the richness of Black American culture cannot be solely defined by what we produce or create, for we are worthy of far more than that, I am an honored to come from and be apart of a legacy as rich as ours.

What To Watch

In the 2021 documentary, Black Art: In the Absence of Light, director and producer Sam Pollard, with the assistance of some of the biggest names in Black art, explores the contributions by Black artists and their place amongst the canon of American art, beginning with the LACMA exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art, curated by David Driskell, up until the contemporary moment.

When this documentary first released, I was finishing my last online semester of undergrad, and was in the thick of submitting grad school applications. And of all the documentaries I would watch during my art history studies, this was the first one I watched that I felt uniquely connected to. Here was a legacy of artists, art historians, and art collectors who looked like me, who have dedicated their lives and work to uplifting the artistic practice of Black people. Which is everything I’ve ever wanted to do.

Featuring the work of artists like Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, Theaster Gates, Richard Mayhew, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker, Sanford Biggers, Kehinde Wiley and more, the film explores the legacies of Black art, connecting artists of the present to the artistic forefathers and mothers. What I love most about the film is that while it highlights Black artists, it is also clear that these artists didn’t just magically appear. That they are connected to a rich history and legacy of artistic practitioners that laid the foundation on which they stand today. Very often, Black (and other marginalized) artists are presented in a context severed from the larger historical canon in art history, especially in academic spaces. And rather than learning about landscape artists like Robert Duncanson alongside artists working in the same tradition, like Thomas Cole of the Hudson River School, art students would have to wait to hear about Duncanson while taking a specialized course on African American/Black art. And even then, it’s unlikely that his work will be presented in a way that contextualizes his art in time, alongside those who are his contemporaries.

And when we talk about legacies and artistic traditions, this is important because when you posit Black artists within the larger art historical canon, you provide Black artists— in various mediums, with a touchpoint or through line, by which they can connect their artistic practice in the present moment to that of the past.

I recommend this documentary to anyone with a love of art, who is interested in artists outside of those traditionally taught or easily found on the walls of prestigious museums, and are looking to expand their knowledge of what American art is.

.

One of the artists featured in Black Art, is one of my favorite painters, Kerry James Marshall.

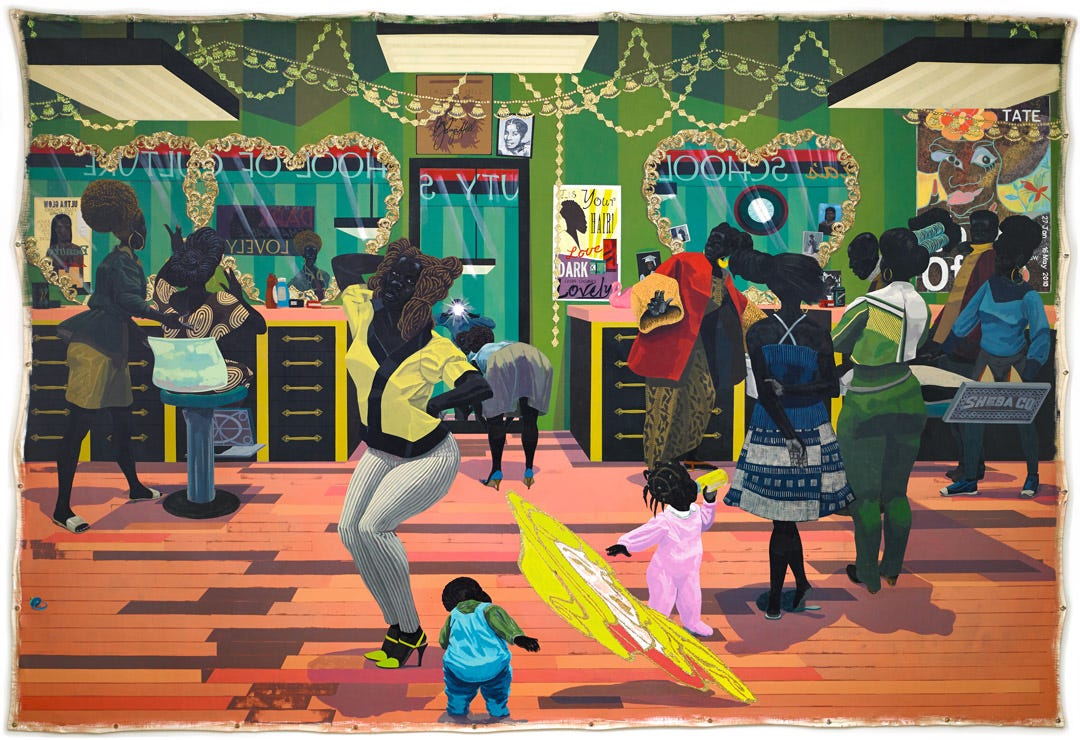

The first time I saw a Kerry James Marshall painting in person was in 2017 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. A 35-year retrospective on Marshall’s artistic practice and work, I was floored when I walked into MOCA’s exhibition space the first time. Known for the “unequivocally Black [and] emphatically Black figures” that populate his pieces, Marshall’s work highlights the beauty in the lives of Black people through the elevation of the ordinary. Whether its going to the hair shop (see: image above} or getting dressed (see: image below) — Marshall affirms that the Black existence is inherently art and is worthy of being uplifted and hanging on the walls of the most important cultural institutions.

It was so beautiful to see the walls of the museum covered in art depicting Black people so vibrantly. Now to know me, is to know that nine times out of ten, I’m going to cry when I go to the museum. Witnessing a beautiful piece of work, observing fellow patrons be enraptured by the beauty around them, experiencing the emotions embedded in the piece itself, it’s all enough to make me teary-eyed, and the first time I beheld School of Beauty, School of Culture, I was rightful moved to tears. The subject of the painting, which is a busy hair salon, brought back childhood memories of going to get my hair done with my mum and aunties, listening in on the ‘grown folks business’ of the women getting their hair done and playing along side other impatient children as we waited for our mum’s to be finished. And while the subject of the painting is ordinary, there is beauty in seeing your existence reflected back at you and uplifted in such a beautiful way.

However, I think what moved me the most about this painting, was the love that was poured into the piece by the artist. It’s his love for his community that drives the kind of work he creates and the subjects he portrays. And it’s this love that I feel looking back at me when I come across his paintings, it seems to bubble up and over, at the edge of every work. In the documentary, Marshall recounts a conversation he had with the painter Charles White, in which he told Marshall: “whenever you make work, it ought to be about something. And it ought to be about something that mattered.” And it’s clear, in every work by Marshall that I come across, that what matters to him is the Black experience and ultimately, Black life.

What To See

Another aspect of the art world, highlighted in the Black Art documentary was the role and importance of art collectors. One of the collectors that the documentary focused in on was Kasseem Dean, better known as Swizz Beatz, the world-renowned hip hop producer. Dean, alongside his wife, Alicia Keys, are the stewards of the Dean Collection— a private collection over 400 works and counting, dedicated to “collect[ing], protect[ing], [and] respect[ing]” Black art and culture, as well as the promotion of living artists.

In the film, artist Glenn Ligon discusses how important it is for collectors, especially those of Black art, to give and loan out works to museums, so that the public is able to engage with the work and the artists who created them. And how this act of cultural philanthropy, inspires and creates future generations of artists.

Most recently, the Brooklyn Museum collaborated with the Deans to open up its latest exhibition: Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys, which features over 100 works by Black artists, both emerging and established. Many of the artists featured in the show, which is now open until July 7th, were also featured in the Black Art doc, like Amy Sherald, Kehinde Wiley, Radcliffe Bailey, and Gordon Parks. Other artists featured include sculptor Kennedy Yanko, photographer Deana Lawson, and visual artist Mickalene Thomas. If you’re in New York, I would highly suggest checking out this show featuring some of best working artists today.

And for my West Coast art besties, be sure to check out The Broad’s next special exhibition, Mickalene Thomas: All About Love, which will open May 25th and run until September 29th. Featuring over 80 works, the show will highlight the last 20 years of Thomas’s artistic practice with pieces in various mediums including: collage, photography and painting. In the shows press release, it is mentioned that the exhibition “shares its title and several of its themes with the pivotal text by feminist author bell hooks, in which love is an active process rooted in healing, carving a path away from domination and towards collective liberation.”

Known for her patchwork paintings and collages, Thomas uses her work to celebrate “female beauty, sexuality, desire, and power,” through Black feminine subjects and makes reference to many well-known art figures such as Matisse, Manet, and Picasso. And in doing so, deconstructs and “re-stages scenes from 19th century” works.

If you’re in L.A., this is a show I would not miss out on!

What To Listen To

Today’s post’s title is inspired by my recent rediscovery of Solange’s A Seat at the Table (2016). On track 13, Solange borrows the company slogan of 90’s hip hop apparel company FUBU, to create an anthem of Black pride, on which she sings “for us, by us.” The song, and subsequently, the entire album is a love letter to Black art, Black love and Blackness as a whole. An album I’ve loved since its release, it’s been on heavy rotation this month and as such, I’ve developed a deeper appreciation for it and the way Solange explores the joy, the love, and the grief that accompanies Blackness.

Other things I’m listening to and loving this month:

Nao’s entire Saturn (2018) album

Aqyila’s latest single Bloom (2024)

BJ The Chicago Kid’s cover of Close (2019) by Ella Mai, which he co-wrote

Eryn Allen Kane’s debut EP Aviary: Act 1 (2015)

Destin Conrad’s Colorway (2021) album

I love, love. In all its many iterations. Namely, love to the point of invention. For example, how the creator of goldfish creating the ‘snack that smiles back’ because his wife was a pisces. And what I love most about Black art, is that its creators were so moved by a love for their community that they saw lacking in representation amongst visual culture, that they set out to fix the canon of art themselves. They embarked on a journey to create art so grand, so Giant, that it could not be ignored — forcing the world — namely the art world, to take notice. Their love has led to the discovery of so many other artists whose names and works would otherwise be lost to history and time, names and works that continue to inspire generations of artists, collectors, and historians, myself included, to create space in rooms which have historically been exclusionary, in order to honor the artisans who came before us and to forge a path for those who are coming upon the horizon. And in the juxtaposition of what has been and what is forthcoming, I have found that even in the absence of light, Black American art, embodies this kind of love.

And this is precisely the kind of love that invigorates me as an art historian and during this month of love, I am reminded just how much I love Black art.

xx gabi